Cast

of Characters

Here are brief bios of some of the amazing cast of characters who have spent years on, in or under global waters. I’ll regularly add to this list, so keep checking for familiar faces.

If you’d like to contact any of them, I’d be happy to pass along your contact information. Please note that the photographs provided here are not for reproduction without permission.

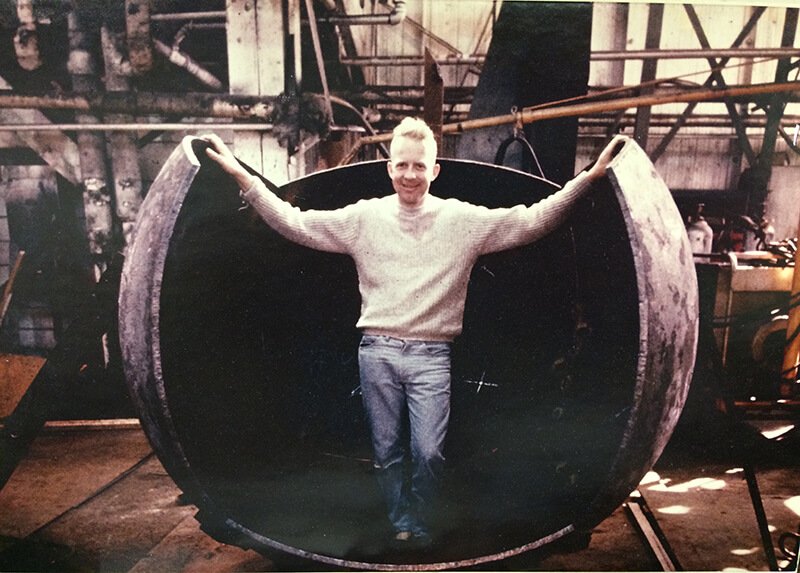

(Photo courtesy of Al Trice)

Al Trice

Al Trice credits his father, a pattern maker, who had a woodworking workshop in the basement and encouraged his son to “mess around with tools” as a five and six-year-old. As a kid, Al knew the effects of the Depression and the Second World War. He joined Army cadets in grade 7 and learned Morse Code, then become a crack shot with an Enfield rifle at Magee Secondary’s indoor shooting range.

Al learned how to sail small sailboats from his father and eventually built his own 15-footer. His dad was a strong believer in a boy earning his own way so Al started with two paper routes, then worked building dingeys at a woodworking shop. He sailed all over Howe Sound when he wasn’t building boats or model airplanes and then later rebuilt and flew a Boeing primary glider. After graduation, Al progressed to working on a small towboat, spent a season at a whaling station and went commercial fishing. He returned home, got married and apprenticed to Star Shipyard. But the lure of scuba diving and salvage work took hold, and he learned hardhat diving, as well, joining the union and becoming a commercial diver.

With many jobs, the challenge was to work ever deeper, but the difficulties and risks were huge. Deeper work also intrigued fellow diver Don Sorte, so he and Al headed to California in search of a small, suitable submarine they could afford. Instead they came back with the realization they were going to have to build it themselves. Fortunately, they also teamed up with Boeing machinist Mack Thomson and the idea for Pisces I was born. The trio formed HYCO as International Hydrodynamics came to be known. Warren Joslyn, a knowledgeable structural engineer from Boeing, also joined the team.

Pisces I would spawn a fleet of similar submersibles that worked globally, and HYCO would serve as the training ground for any number of B.C. subsea workers and inventors. After HYCO closed down, Al Trice eventually moved to International Submarine Engineering (ISE), working on semi-submersibles and AUVs until retiring recently at 91!

Phil Nuytten

Phil Nuytten has garnered an impressive list of awards and distinctions and has been called a lot of things, he chuckles, but “Canada’s own diving’s Renaissance man” may come closest to describing him accurately. Indeed, he’s not only a diver but an inventor, a tech manufacturer, a businessman, an adventurer, underwater explorer, author, owner of Diver Magazine, a songwriter, a collector and a Northwest Coast Native chief and carver. Phil laughs and says it’s all because he has a short attention span so keeps a lot of projects on the go at the same time.

Whatever the cause, it doesn’t hurt that he has a near photographic memory, is a voracious reader, and runs on determination. In 1954, he quit secondary school for a while to start Vancouver Diver’s Supply, Western Canada’s first dive shop. He paid the bills with making wetsuits and doing salvage work. But the most memorable early incident was the collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge while still under construction. Phil was the first diver on site, a horrific experience. “I was just 16 years old and had never even seen a dead body before. All of a sudden, I was surrounded by them.”

Phil went back to secondary school, then taught himself hardhat diving and went to work in underwater construction. He made a reputation for himself, and at the age of 25, he started his own construction company, Canadian Divers, soon shortened to Can-Dive. He teamed up with Lad Handelman and in 1969 they founded Oceaneering International. With ever deeper diving contracts, Phil suggested to his fellow Oceaneering directors that they consider a radically different Atmospheric Diving Suit (ADS) but nobody was interested. Eventually, Can-Dive set up a new company called International Hardsuits, based in North Vancouver, and produced that revolutionary ADS. The next several years were not easy and in 1984, Phil left Oceaneering, using his stock money to repatriate Can-Dive back to Canada.

Phil then began a series of business survival strategies and innovations including the one-person submersible Deep Rover (launched in 1984), several underwater craft for James Cameron’s film The Abyss, and the Newtsuit in 1986. He set up Nuytco Research in 1992, built the submarine rescue vehicle Remora for the Royal Australian Navy, survived a hostile takeover in 1996, developed the DeepWorker and Dual DeepWorker submersibles in 1998, and unveiled a deeper diving Exosuit ADS in 2012. Given his own diving history, he’s proud that his Newtsuit/Exosuit allows a pilot/diver to work at significant depths at normal atmospheric pressure, without any decompression time, and at a vastly reduced cost over standard mixed-gas/decompression set-ups. Most recently, he and his Can-Dive staff have been working on Ironsuit 2000, an even tougher ADS that Phil describes as “a beast,” and the NewtROV Leveller, intended for global navies with smaller budgets. It says a lot about the merits of determination and a short attention span

Al Robinson

Like many a young kid in the era of World War II, Al Robinson built model airplanes and dreamed of flying jets. But poor eyesight cut that dream short, so he dropped out of school in Grade 11 to “build hot roads and custom cars and chase girls,” he says. Al went on to become a truck driver, a carpenter and an auto-body worker. When he joined HYCO, he admits he had absolutely no knowledge of underwater machinery, but was willing and eager to learn.

Shortly after being hired, Al recalls a discussion with HYCO partner and inventor Mack Thomson. “Jesus, Mack, isn’t that impossible?” Al asked. “He gave me the nastiest look and said, ‘That’s not a word we use around here.’” Hired as an assistant hydraulics technician, Al was soon promoted to chief when his boss got fired. And learn he did. Al also adopted the “nothing’s impossible” attitude. Over the years he’s worked with a variety of companies and good engineers who have said, “You can’t do that. It’s not in the book.” Not surprisingly, he connected most with those who affirmed, “Well, that’s not in the book, but let’s figure out how to do it.”

Al met Terry Knight at HYCO, when they were working in side-by-side shop facilities. Terry recalls, “Al was the hydraulics wizard and I was the sparky. We spent a lot of time together, transposing each other’s drawings so I could learn about hydraulics and he picked up on electronics and electrical.” Al also gained underwater experience in the company’s submersibles. After leaving HYCO, he went to work for International Submarine Engineering (ISE) and even designed a manipulator for the WHOI submersible Alvin. Al worked on many projects for Robotic Systems International, including mechanical spiders for a sci-fi movie, and built himself an early prototype of the small Seamor ROV.

In 1989, Terry and Al teamed up again to start the successful Inuktun Services Ltd. as a retirement project. Al spearheaded many of the unique ideas for the company’s specialized miniature ROVs, with contracts from the U.S. Naval Research and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He’s proud that Inuktun’s miniaturized robots were the only ones to find human remains at Ground Zero after the 9/11 attacks. Terry left Inuktun in 2005; Al stayed on until 2014, retiring at 77 to pursue his hobbies.

“Scratch” McDonald

Deloye “Scratch” McDonald and Don Sorte were boyhood buddies in Seattle. Both became scuba divers and worked hard at making a living from day jobs and scuba work on the side. At one point they put an ad in the Seattle paper saying “We do anything, day or night.” Scratch recalls, “We did all sorts of weird things, and even made a few bucks.”

Deloye’s well-known nickname “Scratch” came from a heavy, handknit sweater he always wore under his diving suit for warmth. The sweater featured a large dollar sign that generated his nickname. “Scratch is American slang for money. I had four children and a wife to support, so Don and I were always looking for ways to make a buck doing something. That’s how I got into submarines.” Scratch has already instructed his daughters he wants to be buried in that sweater. “When I go, it goes with me.”

Diving took Don Sorte from Seattle to Vancouver where he, Al Trice and Mack Thomson set up International Hydrodynamics (HYCO, for short) to build the two-man submersible Pisces I. Funding the sub’s construction was the responsibility of Northwest Diving, a commercial diving company that Don set up. At Don’s invitation, Scratch and his family moved to Canada to work. Like many a diver working for Northwest Diving, he also got involved with HYCO, commonly doing whatever was needed in either organization. In fact, Scratch soon began piloting Pisces and other HYCO submersibles on various jobs and also trained other pilots, notably Mike Macdonald. He still loves underwater work and states, “If a guy walked in the door right now and said to me, ‘Hey, do you want to run this submersible?’ I’d say, ‘When do we leave!’”

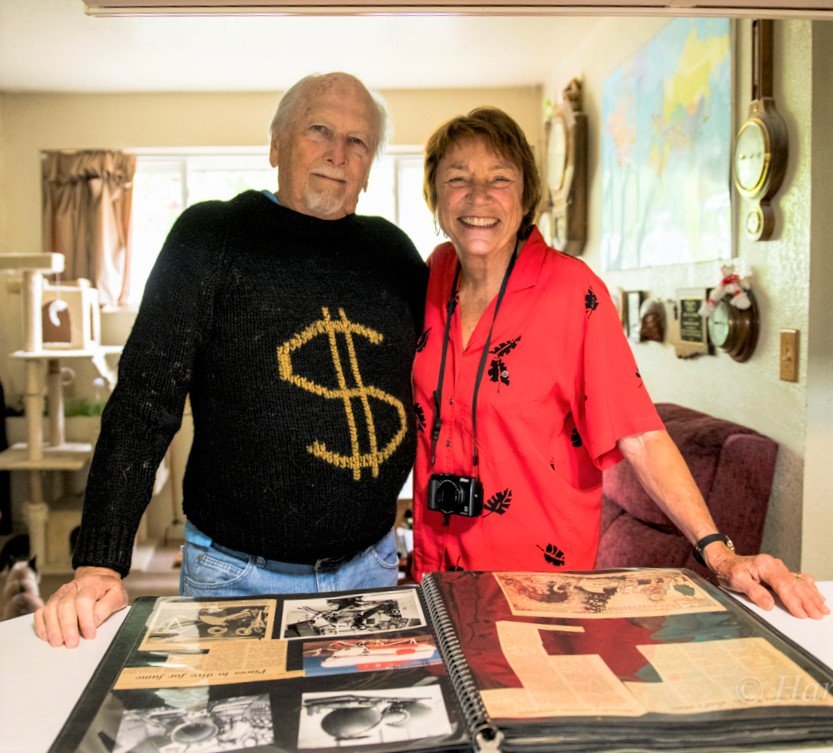

(Photo by Harry Bohm)

Willy Wilhelmsen &

Helmut Lanzinger

Today Willy Wilhelmsen and Helmut Lanzinger are both recognized sonar pioneers in Canada, but both were far from that when they came to Canada as young immigrants. Back then, mastering English and finding work was their first task. They met while working at the Canadian Research Institute in Toronto and separately moved to B.C. in the ‘60s. Willy and Stan Davis started their own company, Aqua Electronics. Helmut unofficially joined in as the company built electromagnetic underwater communication systems—essentially an underwater telephone for diver communication. When there wasn’t money to buy the expensive equipment they needed, they designed it, often in consultation with a bottle of vodka.

Subsequently, Willy started up Subcom Systems and Helmut joined as a partner, along with divers Jim Kail and Matt Matthews. Their tiny Canadian company had some remarkable success selling Subcom systems to the U.S. Navy. Helmut eventually left to begin working with Can-Dive.

Willy’s next business venture was Mesotech Systems with Erling Kristensen, Alan Mulvenna and Bob Asplin. They landed a big contract when the Soviets were in Vancouver for their Pisces submersibles, a contract that really launched the business.

Helmut and Willy collaborated again when Helmut went to work in the Arctic. “Mesotech was doing things that had never been done before, things that Helmut needed in the ice,” employee Gordon Kristensen explains. “Willy would design the equipment, we’d build it, and Helmut would put it to work.” That collaboration continued as Helmut began working and experimenting with Mesotech’s side-scan sonar and positioning equipment. He notes, “Willy and I talked a lot. I provided feedback on the equipment, how it was being used and the way it was working.”

Helmut eventually set up his own company, Offshore Systems Ltd. (OSL). As oil and gas companies began to work further offshore and then moved north, they had to contend with ice in all its forms. Companies desperately needed to “see” the bottom in order to best position a wellhead. Willy came up with a prototype for a profiling sonar. Helmut put it to the test in the Western Arctic, figuring out how to rotate the sonar transducer when ice made towing it impossible. Helmut’s company also came up improved positioning data and equipment for ships operating in shallow, icy conditions, an invention that earned him the Order of Canada. “People talk about us as crazy risktakers, but at the time we didn’t know we were taking risks. We were just trying to make things work.”

In 1988, Willy sent up a new company Imagenex, with a successful global market. Managing Director Gordon Kristensen says, “Today it’s so cliché to say ‘thinking outside the box,’ but that’s exactly what Willy and Helmut did–and still do.”

Mark Atherton

Originally, Mark Atherton intended to be a logger, but a serious altercation with a tree changed that career path. Instead, he switched to commercial diving and got a job with Phil Nuytten’s Can-Dive, doing underwater photography. He jumped at the chance to learn about side-scan sonar under the tutelage of Helmut Lanzinger. The challenge that Helmut set up for his students was to find a sunken tugboat called the Gulf Master that had gone down in the Sechelt area with the loss of five crew members. Earlier searches using a ship’s sounder and magnetometer had been fruitless, so it was a perfect challenge for eager students.

Helmut emphasized the importance of advance research and setting up micro-wave positioning equipment. Helmut also widened what had been the historic search site. With their homework completed, the students launched the side-scan sonar and within hours found the tug. For Mark Atherton it was a life-changing discovery. He distinctly remembers watching a blob appear on the sonar record. Looking at that blurred image, I thought, “This is the most incredible instrument I’ve ever seen.” And then he realized, “This is what I’ve gotta’ do!”

Although Mark is a decade or two younger than sonar pioneers Willy and Helmut, he certainly shares their passion about sonar. Mark gained experience working with Mesotech equipment, and his Can-Dive employment provided a remarkable opportunity for hands-on learning with sonars, submersibles and ROVs. Eventually, he took a job with Simrad Mesotech, a company that decades later morphed into Kongsberg Mesotech. And in 2011, Mark published Echoes and Images, The Encyclopedia of Side Scan and Sonar Scanning Operations, a pragmatic textbook based on his decades of experience and teaching.